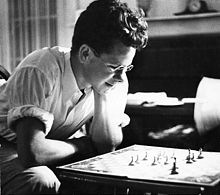

Gordon Gould

Gordon Gould | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Richard Gordon Gould[1] July 17, 1920 |

| Died | September 16, 2005 (aged 85) New York City |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Union College, New York (BS) Yale University (MS) Columbia University (PhD) |

| Known for | Laser, patent law |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | NYU Poly |

Richard Gordon Gould (July 17, 1920 – September 16, 2005) was an American physicist who is sometimes credited with the invention of the laser and the optical amplifier. (Credit for the invention of the laser is disputed, since Charles Townes and Arthur Schawlow were the first to publish the theory and Theodore Maiman was the first to build a working laser). Gould is best known for his thirty-year fight with the United States Patent and Trademark Office to obtain patents for the laser and related technologies. He also fought with laser manufacturers in court battles to enforce the patents he subsequently did obtain.

Early life and education

[edit]

Gould was born in New York City in 1920.[2] He was the oldest of three sons. His father was the founding editor of Scholastic Magazine Publications in New York City.[3] His mother encouraged his interest in inventors such as Thomas Edison and gave him a toy Erector set at an early age.[4] He grew up in Scarsdale, a small suburb of New York, and attended Scarsdale High School. He earned a Bachelor of Science in physics at Union College, where he became a member of the Sigma Chi fraternity, and a master's degree at Yale University, specializing in optics and spectroscopy.[5] Between March 1944 and January 1945 he worked on the Manhattan Project but was dismissed due to his activities as a member of the Communist Political Association.[6] In 1949 Gould went to Columbia University to work on a doctorate in optical and microwave spectroscopy.[7] His doctoral supervisor was Nobel laureate Polykarp Kusch, who guided Gould to develop expertise in the then-new optical pumping technique.[8] In 1956, Gould proposed using optical pumping to excite a maser, and discussed this idea with the maser's inventor Charles Townes, who was also a professor at Columbia and later won the 1964 Nobel prize for his work on the maser and the laser.[9] Townes gave Gould advice on how to obtain a patent on his innovation, and agreed to act as a witness.[10]

Invention of the laser

[edit]| External audio | |

|---|---|

By 1957, many scientists including Townes sought a way to achieve maser-like amplification of visible light. In November of that year, Gould realized that one could make an appropriate optical resonator by using two mirrors as a Fabry–Pérot interferometer. Unlike previously considered designs, this approach would produce a narrow, coherent, intense beam. Since the sides of the cavity did not need to be reflective, the gain medium could easily be optically pumped to achieve the necessary population inversion. Gould also considered pumping of the medium by atomic-level collisions, and anticipated many of the potential uses of such a device.

Gould recorded his analysis and suggested applications in a laboratory notebook under the heading "Some rough calculations on the feasibility of a LASER: Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation"—the first recorded use of this acronym.[11] Gould's notebook was the first written prescription for making a viable laser and, realizing what he had in hand, he took it to a neighborhood store to have his work notarized. Arthur Schawlow and Charles Townes independently discovered the importance of the Fabry–Pérot cavity—about three months later—and called the resulting proposed device an "optical maser".[12] Gould's name for the device was first introduced to the public in a conference presentation in 1959, and was adopted despite resistance from Schawlow and his colleagues.[13][14]

Eager to achieve a patent on his invention, and believing incorrectly that he needed to build a working laser to do this, Gould left Columbia without completing his doctoral degree and joined a private research company, TRG (Technical Research Group).[15] He convinced his new employer to support his research, and they obtained funding for the project from the Advanced Research Projects Agency, with support from Charles Townes.[16] Unfortunately for Gould, the government declared the project classified, which meant that a security clearance was required to work on it.[17] Because of his former participation in communist activities, Gould was unable to obtain a clearance. He continued to work at TRG, but was unable to contribute directly to the project to realize his ideas. Due to technical difficulties and perhaps Gould's inability to participate, TRG was beaten in the race to build the first working laser by Theodore Maiman at Hughes Research Laboratories.

Battles for patents

[edit]During this time, Gould and TRG began applying for patents on the technologies Gould had developed. The first pair of applications, filed together in April 1959, covered lasers based on Fabry–Pérot optical resonators, as well as optical pumping, pumping by collisions in a gas discharge (as in helium–neon lasers), optical amplifiers, Q-switching, optical heterodyne detection, the use of Brewster's angle windows for polarization control, and applications including manufacturing, triggering chemical reactions, measuring distance, communications, and lidar. Schawlow and Townes had already applied for a patent on the laser, in July 1958. Their patent was granted on March 22, 1960. Gould and TRG launched a legal challenge based on his 1957 notebook as evidence that Gould had invented the laser prior to Schawlow and Townes's patent application. (At the time, the United States used a first to invent system for patents.) While this challenge was being fought in the Patent Office and the courts, further applications were filed on specific laser technologies by Bell Labs, Hughes Research Laboratories, Westinghouse, and others. Gould ultimately lost the battle for the U.S. patent on the laser itself, primarily on the grounds that his notebook did not explicitly say that the sidewalls of the laser medium were to be transparent, even though he planned to optically pump the gain medium through them, and considered loss of light through the sidewalls by diffraction.[18] Questions were also raised about whether Gould's notebook provided sufficient information to allow a laser to be constructed, given that Gould's team at TRG was unable to do so.[19] Gould was able to obtain patents on the laser in several other countries; however, he continued fighting for U.S. patents on specific laser technologies for many years afterward.[19]

In 1967, Gould left TRG and became a professor at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, now New York University Tandon School of Engineering.[20] While there, he proposed many new laser applications, and arranged government funding for laser research at the institute.

Gould's first laser patent was awarded in 1968, covering an obscure application—generating X-rays using a laser. The technology was of little value, but the patent contained all the disclosures of his original 1959 application, which had previously been secret. This allowed the patent office greater leeway to reject patent applications that conflicted with Gould's pending patents.[21] Meanwhile, the patent hearings, court cases, and appeals on the most significant patent applications continued, with many other inventors attempting to claim precedence for various laser technologies. The question of just how to assign credit for inventing the laser remains unresolved by historians.[22][23]

By 1970, TRG had been bought by Control Data Corporation, which had little interest in lasers and was disposing of that part of the business.[24] Gould was able to buy back his patent rights for a thousand dollars, plus a small fraction of any future profits.

In 1973, Gould left the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn to help found Optelecom, a company in Gaithersburg, Maryland that makes fiberoptic communications equipment.[25] He later left his successful company in 1985.

Further patent battles, and enforcement of issued patents

[edit]Shortly after starting Optelecom, Gould and his lawyers changed the focus of their patent battle. Having lost many court cases on the laser itself, and running out of appeal options, they realized that many of the difficulties could be avoided by focusing instead on the optical amplifier, an essential component of any laser.[26] The new strategy worked, and in 1977 Gould was awarded U.S. patent 4,053,845, covering optically pumped laser amplifiers. By then, the laser industry had grown to annual sales of around $400 million, rebelled at paying royalties to license the technology they had been using for years, and fought in court to avoid paying.

The industry outcry caused the patent office to stall on releasing Gould's other pending patents, leading to more appeals and amendments to the pending patents.[27] Despite this, Gould was issued U.S. patent 4,161,436 in 1979, covering a variety of laser applications including heating and vaporizing materials, welding, drilling, cutting, measuring distance, communication systems, television, laser photocopiers and other photochemical applications, and laser fusion.[28] The industry responded with lawsuits seeking to avoid paying to license this patent as well. Also in 1979, Gould and his financial backers founded the company Patlex, to hold the patent rights and handle licensing and enforcement.[29]

The legal battles continued, as the laser industry sought to not only prevent the Patent Office from issuing Gould's remaining patents, but also to have the already-issued ones revoked. Gould and his company were forced to fight both in court, and in Patent Office review proceedings. According to Gould and his lawyers, the Office seemed determined to prevent Gould from obtaining any more patents, and to rescind the two that had been granted.[30]

Things finally began to change in 1985. After years of legal process, the Federal Court in Washington, D.C. ordered the Patent Office to issue Gould's patent on collisionally pumped laser amplifiers. The Patent Office appealed, but was ultimately forced to issue U.S. patent 4,704,583, and to abandon its attempts to rescind Gould's previously issued patents.[31] The Brewster's angle window patent was later issued as U.S. patent 4,746,201.

The end of the Patent Office action freed Gould's enforcement lawsuits to proceed. Finally, in 1987, Patlex won its first decisive enforcement victory, against Control Laser corporation, a manufacturer of lasers.[32] Rather than be bankrupted by the damages and the lack of a license to the technology, the board of Control Laser turned ownership of the company over to Patlex in a settlement deal. Other laser manufacturers and users quickly agreed to settle their cases and take out licenses from Patlex on Patlex's terms.

The thirty year patent war that it took for Gould to win the rights to his inventions became known as one of the most important patent battles in history. In the end, Gould was issued forty-eight patents, with the optical pumping, collisional pumping, and applications patents being the most important.[33] Between them, these technologies covered most lasers used at the time. For example, the first operating laser, a ruby laser, was optically pumped; the helium–neon laser is pumped by gas discharge.

The delay—and the subsequent spread of lasers into many areas of technology—meant that the patents were much more valuable than if Gould had won initially. Even though Gould had signed away eighty percent of the proceeds to finance his court costs, he made several million dollars.[34]

"I thought that he legitimately had a right to the notion to making a laser amplifier", said William R. Bennett, who was a member of the team that built the first laser that could fire continuously. "He was able to collect royalties from other people making lasers, including me."[34]

Election to Hall of Fame and death

[edit]Even though his role in the invention of the laser was disputed over decades, Gould was elected to the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1991.[34]

Gould died of natural causes on September 16, 2005.[34] He was 85.[35] At the time of his death, Gould's role in the invention continued to be disputed in scientific circles.[34] Apart from the dispute, Gould had realized his hope to "be around" when the Brewster's angle window patent expired in May 2005.[36]

See also

[edit]- Robert Kearns, another inventor who fought a long battle to enforce his patents.

- Edwin H. Armstrong, another inventor who fought a long and acrimonious battle to enforce his patents.

References and citations

[edit]- Taylor, Nick (2000). LASER: The inventor, the Nobel laureate, and the thirty-year patent war. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83515-0. OCLC 122973716.

- Brown, Kenneth (1987). Inventors at Work: Interviews with 16 Notable American Inventors. Redmond, Washington: Tempus Books of Microsoft Press. ISBN 1-55615-042-3. OCLC 16714685.

- ^ Bernstein, Adam (2005-09-20). "Laser Pioneer Gordon Gould Dies at 85". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Gordon Gould". Lemelson. 2005-09-16. Retrieved 2025-01-10.

- ^ Taylor (2000), p. 14.

- ^ Reed, Christopher (2005-09-27). "Obituary: Gordon Gould". the Guardian. Retrieved 2025-01-10.

- ^ Taylor (2000), p. 16–20.

- ^ Taylor (2000), p. 19–25.

- ^ Taylor (2000), p. 37–40.

- ^ Taylor (2000), p. 45, 56.

- ^ "Nobel Prize in Physics 1964". The Nobel Prize Organisation. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ Taylor (2000), p. 62.

- ^ Taylor (2000), pp. 66–70.

- ^ Schawlow, Arthur L.; Townes, Charles H. (December 1958). "Infrared and optical masers". Physical Review. 112 (6–15): 1940–1949. Bibcode:1958PhRv..112.1940S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.112.1940.

- ^ Gould, R. Gordon (1959). "The LASER, Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation". In Franken, P.A.; Sands R.H. (eds.). The Ann Arbor Conference on Optical Pumping, the University of Michigan, June 15 through June 18, 1959. p. 128. OCLC 02460155.

- ^ Chu, Steven; Townes, Charles (2003). "Arthur Schawlow". In Edward P. Lazear (ed.). Biographical Memoirs. vol. 83. National Academy of Sciences. p. 202. ISBN 0-309-08699-X.

- ^ Taylor (2000), pp. 72–3.

- ^ Taylor (2000), pp. 74–90.

- ^ Taylor (2000), pp. 92–6.

- ^ Taylor (2000), pp. 159, 173.

- ^ a b Taylor (2000).

- ^ Taylor (2000), pp. 172–5.

- ^ Taylor (2000), p. 180.

- ^ Bromberg, Joan Lisa (1991). The Laser in America, 1950–1970. MIT. pp. 74–77. ISBN 978-0-262-02318-4.

- ^ Spencer Weart, Center for History of Physics (2010). "Who Invented the Laser?". Bright Idea: The First Lasers. American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on May 28, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ^ Taylor (2000), pp. 190–3.

- ^ Taylor (2000), pp. 197–201.

- ^ Taylor (2000), pp. 199–212.

- ^ Taylor (2000), p. 218.

- ^ Taylor (2000), p. 220–2.

- ^ Taylor (2000), p. 221–3.

- ^ Taylor (2000), pp. 237–247.

- ^ Taylor (2000), pp. 280–3.

- ^ Taylor (2000), pp. 280–5.

- ^ Taylor (2000), p. 284.

- ^ a b c d e Chang, Kenneth (September 20, 2005). "Gordon Gould, 85, Figure In Invention of the Laser". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (2005-09-20). "Gordon Gould, 85, Figure in Invention of the Laser, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 2025-01-10.

- ^ Taylor (2000), p. 285.

External links

[edit]- Bright Idea: The First Lasers Archived 2014-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

- 1920 births

- 2005 deaths

- 20th-century American inventors

- Columbia University alumni

- Discovery and invention controversies

- Union College (New York) alumni

- Yale University alumni

- People from Scarsdale, New York

- Laser researchers

- Scarsdale High School alumni

- Polytechnic Institute of New York University faculty

- Manhattan Project people