Cascais

Cascais | |

|---|---|

|

Clockwise: Along the coast west of Boca do Inferno; Palacete Seixas; King Carlos I Ave.; Praia do Guincho; Marechal Carmona Park; View of Cascais and Estoril. | |

| |

| Coordinates: 38°42′N 9°25′W / 38.700°N 9.417°W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Lisbon |

| Metropolitan area | Lisbon |

| District | Lisbon |

| Parishes | 4 |

| Government | |

| • President | Carlos Carreiras (PSD-CDS–PP) |

| Area | |

• Total | 97.40 km2 (37.61 sq mi) |

| Population (2021) | |

• Total | 214,158 |

| • Density | 2,200/km2 (5,700/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+00:00 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+01:00 (WEST) |

| Postal code | 2750 |

| Area code | 214 |

| Patron | Saint Anthony |

| Website | www |

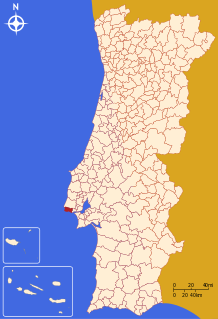

Cascais (European Portuguese pronunciation: [kɐʃˈkajʃ] ⓘ) is a town and municipality in the Lisbon District of Portugal, located on the Portuguese Riviera. The municipality has a total of 214,158 inhabitants[1] in an area of 97.40 km2.[2] Cascais is an important tourist destination. Its marina hosts events such as the America's Cup and the town of Estoril, part of the Cascais municipality, hosts conferences such as the Horasis Global Meeting.

Cascais's history as a popular seaside resort originated in the 1870s, when King Luís I of Portugal and the Portuguese royal family made the seaside town their residence every September, thus also attracting members of the Portuguese nobility, who established a summer community there. Cascais is known for the many members of royalty who have lived there, including King Edward VIII of the United Kingdom, when he was the Duke of Windsor, King Juan Carlos I of Spain, and King Umberto II of Italy. Exiled Cuban president Fulgencio Batista was also once a resident of the municipality. The Casino Estoril inspired Ian Fleming's first James Bond novel, Casino Royale.[3]

The municipality is one of the wealthiest in both Portugal and the Iberian Peninsula.[4][5][6][7] It has one of the most expensive real estate markets and one of the highest costs of living in the country,[8][9][10][11] and is consistently ranked highly for its quality of life.[12][13]

History

[edit]

Human settlement of the territory today known as Cascais dates to the late Paleolithic, as indicated by remnants encountered in the north of Talaíde, in Alto do Cabecinho (Tires) and south of Moinhos do Cabreiro.[14] It was during the Neolithic that permanent settlements were established in the region, their inhabitants utilizing the natural grottoes (such as the Caves of Poço Velho in Cascais) and artificial shelters (like those in Alapraia or São Pedro) to deposit their dead. The bodies were buried along with offerings, a practice that continued to the Chalcolithic.[14]

Roman interventions in the area occurred with the settlement of the villae of Freiria (today São Domingos de Rana) and Casais Velhos (Charneca), evidence for which includes a group of ten tanks discovered along the Rua Marques Leal Pancada in Cascais, which was the location of a salting factory for fish.[14] Roman dominion over the territory also influenced place names in the region, as was the case with the word "Caparide" (from the Latin capparis, meaning "caper"), as well as several inscriptions associated with funerary graves.[14]

The Visigoths also left their mark especially on the Visigothic Cemetery of Alcoitão,[15] as well as in the late-Roman and medieval necropolis of Talaíde.[16][17]

Similarly, Muslim settlers in the region left their mark on local place names, including "Alcoitão" and "Alcabideche", where the romantic poet Ibn Muqana al-Qabdaqi, who wrote of the region's agriculture and windmills, was born at the beginning of the 11th century.[14] The discovery of several corpses in 1987 at Arneiro, in Carcavelos, led to the identification of fifteen burials that, due to their characteristics, made it possible to verify that the individuals buried there were of Berber origin.[18]

The development of Cascais began in earnest in the 12th century, when it was administratively subordinate to the town of Sintra, located to the north. In its humble beginnings, Cascais depended on the products of the sea and land, but by the 13th century its fish production was also supplying the nearby city of Lisbon. The toponym "Cascais" appears to derive from this period, a plural derivation of cascal (monte de cascas) which signified a "mountain of shells", referring to the abundant volume of marine mollusks harvested from the coastal waters.[14] During the 14th century, the population spread outside the walls of its fortress castle.

The settlement's prosperity led to its administrative independence from Sintra in 1364. On 7 June 1364, the people of Cascais obtained from King Peter I the elevation of the village to the status of town, necessitating the appointment of local judges and administrators. The townspeople were consequently obligated to pay the Crown 200 pounds of gold annually, as well as bearing the expense of paying the local administrators' salaries. Owing to the regions' wealth, these obligations were easily satisfied.[14] The town and the surrounding lands were owned by a succession of feudal lords, the most famous of whom was João das Regras (died 1404), a lawyer and professor of the University of Lisbon who was involved in the ascension of King John I to power as the first King of the House of Aviz.

The castle of Cascais was likely constructed during this period, since by 1370, King Ferdinand had donated the castle and Cascais to Gomes Lourenço de Avelar to hold as a seigneurial fiefdom.[14] These privileges were then passed on to his successors, among them João das Regras and the Counts of Monsanto, and later the Marquess of Cascais.[14] Meanwhile, despite its conquest and sack by Castilian forces in 1373, and blockade of the port in 1382 and 1384, Cascais continued to grow beyond its walls.[14] By the end of the 14th century this resulted in the creation of the parishes of Santa Maria de Cascais, São Vicente de Alcabideche and São Domingos de Rana.[14]

From the Middle Ages onward, Cascais depended on fishing, maritime commerce (it was a stop for ships sailing to Lisbon), and agriculture, producing wine, olive oil, cereals, and fruits. Due to its location at the mouth of the Tagus estuary, it was also seen as a strategic post in the defence of Lisbon. Around 1488, King John II built a small fortress in the town, situated by the sea. On 15 November 1514, Manuel I conceded a foral (charter) to Cascais, instituting the region's municipal authority.[14] It was followed on 11 June 1551 by a license from King John III to institutionalise the Santa Casa da Misericórdia de Cascais.[14] The Mother Church of Cascais, the Church of Nossa Senhora da Assunção, dates back to the early 16th century. The town's medieval fortress was inadequate to repel invasions, and in 1580 Spanish troops led by the Duque of Alba took the village during the conflict that led to the union of the Portuguese and Spanish crowns. The fortress was enlarged towards the end of the 16th century by King Philip I (Philip II of Spain), turning it into a typical Renaissance citadel with the characteristic flat profile and star-shaped floorplan. Following the Portuguese restoration in 1640, a dozen bulwarks and redoubts were constructed under the direction of the Count of Cantanhede, who oversaw the defences of the Tagus estuary, the gateway to the city of Lisbon.[14] Of these structures, the citadel of Cascais, which was constructed alongside the fortress of Our Lady of Light, considerably reinforced the strategic defences of the coast.[14]

In 1755, the great Lisbon earthquake destroyed a large portion of the city. Around 1774, the Marquis of Pombal, prime-minister of King José I, took protective measures for the commercialisation of the wine of Carcavelos and established the Royal Factory of Wool in the village, which existed until the early 19th century. During the invasion of Portugal by Napoleonic troops in 1807, the citadel of Cascais was occupied by the French, with General Junot staying some time in the village.

In 1862, the Visconde da Luz built a summer house in Cascais. He and a group of friends also organized the construction of a road from Cascais to Oeiras, effectively linking Cascais to Lisbon, and also promoted other improvements to the town. As a result of these improvement, King Luís I decided to make Cascais into his summer residence and, from 1870 to 1908, the Portuguese royal family from the House of Braganza-Saxe-Coburg and Gotha spent part of the summer in Cascais to enjoy the sea, turning the quiet fishing village into a cosmopolitan address. Thanks to King Luís, the citadel was equipped with the country's first electric lights in 1878. Cascais also benefited from the construction of a better road to Sintra, a bullfight ring, a sports club, and improvements to basic infrastructure for the population. Many noble families built impressive mansions in an eclectic style commonly referred to as summer architecture, many of which are still to be seen in the town centre and environs. The first railway arrived in 1889. Another important step in the development of the area was made in the first half of the 20th century with the building of a casino and infrastructure in neighbouring Estoril.

In 1882 Cascais installed one of the first tide gauges in Europe in order to assist with navigation into the port of Lisbon. In 1896, King Carlos I, a lover of all maritime activities, installed in the citadel the first oceanographic laboratory in Portugal. The King himself led a total of 12 scientific expeditions to the coast; these ended in 1908 after his assassination in Lisbon.

Due to Portugal's neutrality in World War II and the town's elegance and royal past, Cascais became home to many of the exiled royal families of Europe, including those of Spain (House of Bourbon), Italy (House of Savoy), Hungary and Bulgaria. Their stories are told at the Exiles Memorial Centre.

Nowadays, Cascais and its surroundings are a popular vacation spot for the Portuguese as well as for the international jet set and regular foreign tourists, all of them drawn by its fine beaches. The town hosts many international events, including sailing and surfing. In 2018 it was the European Youth Capital.

Geography

[edit]

Cascais is situated on the western edge of the Tagus estuary, between the Sintra mountains and the Atlantic Ocean; the territory occupied by the municipality is limited in the north by the municipality of Sintra, south and west by the ocean, and east by the municipality of Oeiras.[14]

Administratively, the municipality is divided into 4 civil parishes (freguesias),[19] with municipal authority vested in the Câmara Municipal of Cascais:

Cascais' coastline is home to 17 beaches.[20] These are:

- Praia das Avencas

- Praia da Azarujinha

- Praia da Bafureira

- Praia da Conceição

- Praia da Cresmina

- Praia da Duquesa

- Praia da Parede

- Praia da Poça

- Praia da Rainha

- Praia da Ribeira de Cascais

- Praia das Moitas

- Praia de Carcavelos

- Praia de S. Pedro do Estoril

- Praia de Santa Marta

- Praia do Abano

- Praia do Tamariz

- Praia do Guincho

Guincho Beach and Carcavelos Beach are especially well known as good surf spots. Close to Praia do Guincho is the Cresmina Dune, which is an unstable dune system due to the constant drifting of sand particles caused by strong winds.

Climate

[edit]Cascais has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csb) with mild, wet winters and warm, dry summers. Moderated by the Atlantic and the typical urban heat island of a city, temperatures in Cascais rarely get below 5 °C (41 °F) or above 30 °C (86 °F).

| Climate data for Monte Estoril, 1931-1960 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.0 (71.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

27.6 (81.7) |

32.1 (89.8) |

34.0 (93.2) |

39.2 (102.6) |

38.9 (102.0) |

39.5 (103.1) |

35.3 (95.5) |

34.8 (94.6) |

28.2 (82.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

39.5 (103.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 14.9 (58.8) |

15.8 (60.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.9 (76.8) |

22.0 (71.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

20.4 (68.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.8 (53.2) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.0 (57.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.6 (67.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.7 (71.1) |

20.8 (69.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.7 (62.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 8.6 (47.5) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

17.4 (63.3) |

16.8 (62.2) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −0.3 (31.5) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

3.1 (37.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

8.3 (46.9) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 97.0 (3.82) |

67.6 (2.66) |

91.0 (3.58) |

49.6 (1.95) |

38.0 (1.50) |

13.0 (0.51) |

2.4 (0.09) |

4.4 (0.17) |

28.6 (1.13) |

68.4 (2.69) |

82.3 (3.24) |

93.9 (3.70) |

636.2 (25.04) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 14 | 11 | 14 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 106 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 77 | 78 | 73 | 74 | 74 | 71 | 73 | 75 | 76 | 79 | 81 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 161.1 | 183.0 | 209.1 | 275.7 | 315.6 | 342.8 | 383.7 | 356.6 | 279.1 | 234.9 | 184.2 | 162.8 | 3,088.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 53 | 60 | 56 | 70 | 71 | 77 | 85 | 84 | 75 | 68 | 61 | 55 | 68 |

| Source: Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera[21][22] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: INE[23] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]

Cascais is easily reached from Lisbon by car on the A5 Lisbon-Cascais highway, or alternatively on the scenic "marginal" road, as well as by frequent inexpensive commuter trains. Taxis are also a common and inexpensive mode of transport in the area. The city has the ruins of a castle, an art museum and an ocean museum, as well as parks and the cobbled streets of the historic centre. The town has many hotels and tourist apartments as well as many good restaurants of varying cost. It is a fine base to use for those visiting Lisbon and its environs who prefer to stay outside of the city.

Cascais ranks 9th in population density and 6th in percentage of population employed among Portuguese municipalities.[24]

Cascais is surrounded by popular beaches. Guincho Beach to the northwest is primarily a surfing, windsurfing, and kitesurfing beach because of the prevailing winds and sea swells, while the calm waters of the beaches to the east attract sunbathers. The lush Sintra mountains to the north are a further attraction. The shoreline to the west has cliffs, attracting tourists who come for the panoramic views of the sea and other natural sights such as the Boca do Inferno. It is also becoming a popular golf destination, with over 10 golf courses nearby.

A large marina with 650 berths was opened in 1999 and has since held many sailing events. It was the official host of the 2007 ISAF Sailing World Championships for dinghies and racing yachts. The municipality also hosts international tennis and motorcycling events and for many years hosted the FIA F1 Portugal Grand Prix at the Estoril race track. The Estoril Casino is one of the largest in Europe. Near the casino is the "Hotel Palácio" (Palace Hotel), where scenes of the James Bond movie On Her Majesty's Secret Service were shot.

In 2017 the municipality started charging a small tourist tax, as the city had become one of the most visited destinations in Portugal. It is estimated that around 1.2 million tourists stay in the city's hotels each year (2016).[25]

The Cascais Aerodrome in Tires (São Domingos de Rana) serves general aviation and also offers domestic scheduled flights by Aero VIP.

Education

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2016) |

The Carcavelos community houses the Saint Julian's School, a British international school.

The Estoril community hosts a kindergarten and elementary school campus of the German School of Lisbon.[26]

Outeiro de Polima, São Domingos de Rana, in Cascais, houses Saint Dominic's International School.[27]

Culture

[edit]The Gil Vicente theatre dates back to 1869. In its early years it was frequently attended by Portugal's royal family. The Cascais Experimental Theatre was established in 1965 and has presented more than a hundred shows since then. Over the years Cascais has developed several art galleries and museums. These are concentrated in a relatively small area of the town, mainly in parkland. Combined, they are known as The Museum Quarter.[28] Several occupy large buildings that were formerly private residences and were subsequently taken over and restored by the Municipality. Entrance is either free or for a small fee (usually not more than €4). The galleries and museums are:

Art galleries

- Casa das Histórias Paula Rego. This is a relatively modern museum devoted to the paintings of Paula Rego and her husband Victor Willing.

- Cascais Cultural Centre. Located on the site of the former convent of Our Lady of Mercy, this colourful building houses rotating exhibitions and also has a small concert hall.[29]

- Casa Duarte Pinto Coelho. The former guardhouse of the Condes de Castro Guimarães Palace, this building houses the Duarte Pinto Coelho art collection.[30]

- Cidadela Arts Centre. This occupies a small part of the Citadel of Cascais and offers space for artists to display and sell their work.

Museums

- The Exiles Memorial Centre is located on the first floor of the iconic modernist building that houses the Estoril post office. It is a history museum which focuses on the lives of the refugees, exiles, and notables who came through Portugal and Cascais during the Second World War.

- The Cascais Citadel Palace Museum is situated inside the grounds of the Citadel. It was used as the summer residence of the royal family from 1870 until 1908, and was subsequently used as one of the official residences of Portuguese presidents. After extensive restoration it was opened as a museum in 2011, with an emphasis on the role of Portuguese presidents.

- Condes de Castro Guimarães Museum. This was built as an aristocrat's summer residence and became a museum in 1931. The building follows an eclectic architectural style, while the museum includes paintings, furniture, porcelain, jewellery and a neo-Gothic organ.

- Casa de Santa Maria. This was built for the same person as the building housing the Condes de Castro Guimarães Museum. Both are built on the banks of a small sea cove. It was acquired by the Cascais Municipality in October 2004 and is interesting mainly for the design and the wall tiles.

- Lighthouse museum. This is built into the Santa Marta Lighthouse, next to the Casa de Santa Maria. Examples of lighthouse lens and other technology can be seen and at certain times the lighthouse can be climbed.

- Casa Sommer is a distinguished private residence converted into a historical museum. It also houses the Municipal Archives. It is the newest museum in the Quarter, having been opened in 2016.

- King D. Carlos Sea Museum was inaugurated in 1992. It has a variety of exhibitions reflecting the origins of Cascais as a fishing village.

- Town museum (Portuguese: Museu da Vila). Provides an introduction to the history of the town.[31]

International relations

[edit] Biarritz, France, since 1986

Biarritz, France, since 1986 Vitória, Brazil, since 1986

Vitória, Brazil, since 1986 Santana, São Tomé and Príncipe, since 1986

Santana, São Tomé and Príncipe, since 1986 Atami, Japan, since 1990

Atami, Japan, since 1990 Wuxi, China, since 1993

Wuxi, China, since 1993 Sal, Cape Verde, since 1993

Sal, Cape Verde, since 1993 Gaza City, Palestine, since 2000

Gaza City, Palestine, since 2000 Guarujá, Brazil, since 2000

Guarujá, Brazil, since 2000 Xai-Xai, Mozambique, since 2000

Xai-Xai, Mozambique, since 2000 Sausalito, United States, since 2012

Sausalito, United States, since 2012 Ungheni, Moldova, since 2012

Ungheni, Moldova, since 2012 Campinas, Brazil, since 2012

Campinas, Brazil, since 2012 Sinaia, Romania, since 2018

Sinaia, Romania, since 2018 Pampilhosa da Serra, Portugal, since 2018

Pampilhosa da Serra, Portugal, since 2018 Bucha, Ukraine, since 2022

Bucha, Ukraine, since 2022

Notable residents

[edit]

- Joaquim António Velez Barreiros (1802–1865). As the Visconde da Luz, is celebrated in Cascais with two streets and a park named after him

- José de Freitas Ribeiro (1868–1929) Portuguese Navy officer, Governor-General of Mozambique, 1910-1911 and Governor-General of Portuguese India, 1917-1919

- Ricardo Espírito Santo (1900-1955) a banker, economist, patron of the arts, international athlete & friend of António de Oliveira Salazar and President of Banco Espírito Santo

- António da Mota Veiga (1915–2005) a politician and former Minister and law professor

- Nadir Afonso (1920 - 2013 in Cascais), a geometric abstractionist painter, notable for his City Series artwork

- John Tojeiro (1923–2005) known at Toj, an engineer and racing car designer

- Francisco Pinto Balsemão (born 1937) a former Prime Minister of Portugal, 1981-1983

- José Luis Encarnação (born 1941) a computer scientist and senior academic in Germany

- Pedro Cardoso (born 1962), Brazilian actor, writer and comedian

- Manuela Carneiro da Cunha (born 1943) a Portuguese-Brazilian anthropologist, studies indigenous people in Brazil.

- Ricardo Salgado (born 1944) an economist and banker, president of Banco Espírito Santo

- Julião Sarmento (1948–2021) a multimedia artist and painter; lived and worked in Estoril

- Manuel Ulrich Garnel (born 1969) a Portuguese logicist who first discovered The Brajevska Polynomial in Cascais, circa 1992

- Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa (born 1948), a Portuguese politician, former Minister, law professor, former journalist, political analyst and current President of Portugal since 2016

- Manuel Botelho (born 1950) a Portuguese artist who lives and works in Estoril

- Ana Gomes (born 1954) a Portuguese former diplomat and politician

- Isabel Jonet (born 1960) president of the Portuguese Federation of Food Banks

- Aure Atika (born 1970) a French actress, writer and director.[33]

- Chabeli Iglesias (born 1971) a Spanish journalist and socialite, daughter of Julio Iglesias

- Luana Piovani (born 1976), a Brazilian actress and former model.[34]

- Diogo Machado (born 1980) known as Add Fuel, a Portuguese visual artist and illustrator

- Ricardo Baptista Leite (born 1980) a doctor, academic, politician and author

- Daniela Ruah (born 1983, Boston, Massachusetts), a Portuguese-American actress, brought up in Portugal, currently starring in the TV series NCIS: Los Angeles.[35]

- Vera Kolodzig (born 1985) a Portuguese actress, brought up in Cascais.[36]

- Ana Gomes Ferreira (born 1987) known as Ana Free, singer/songwriter made popular by YouTube

- Mariana Bandhold (born 1995) a Portuguese-American singer, actress, and songwriter.[37]

Sport

[edit]- Nuno Durão (born 1962) a Portuguese rugby union footballer and coach with 44 caps for Portugal

- Fernando Gonçalves (born 1967) a former footballer with 43 goals

- Paulo Ferreira (born 1979) a former footballer with 306 club caps and 62 for Portugal

- Duarte Félix da Costa (born 1985) racing car driver

- António Félix da Costa (born 1991) racing car driver a former Red Bull test driver and the 2020 Formula E Champion

- Camilla Kemp (born 1996) is an Olympic surfer who competed for Germany[38]

- Fernando Varela (born 1987) a footballer with over 350 club caps and 49 for Cape Verde

- Frederico Morais (born 1992) a surfer in the World Surf League

- Teresa Bonvalot (born 1999) a surfer in the World Surf League the 2016 and 2017 European Junior Champion and 2021-22 WSL Qualifying Series European Champion

Royalty

[edit]

- King Luís I of Portugal (1838 – 1889 in Cascais) a member of the ruling House of Braganza and King of Portugal from 1861 to 1889.

- King Carol II of Romania (1893–1953) and Miklós Horthy (1868–1957), Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary, both lived and died in Estoril, in Cascais.

- Edward, Duke of Windsor (1894–1972) formerly Edward VIII during his brief reign as British King and his wife Wallis, Duchess of Windsor (1896–1986), stayed in Cascais in July 1940 waiting for a ship to the Bahamas.

- King Umberto II of Italy (1904–1983) the last Italian monarch until a referendum ended the Italian monarchy in 1946. He lived the rest of his life at Cascais.

- Prince Juan of Spain, Count of Barcelona (1913–1993), (son of the King Alfonso XIII of Spain and Princess Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg), the designated heir to the Spanish throne, also lived in the municipality of Cascais with his family. Prince Juan's son, future King Juan Carlos I of Spain (born 1938) lived his childhood in exile in Estoril, while his youngest brother Prince Alfonso of Bourbon (1941–1956) died there and was originally buried in Cascais.

- Luisa Isabel Álvarez de Toledo, 21st Duchess of Medina Sidonia (1936–2008) holder of the Dukedom of Medina Sidonia in Spain.

- Tsar Simeon II of Bulgaria (born 1937), arrived in the municipality, with his mother Tsarina Giovanna of Italy (1907-2000) who died in Estoril.[39] He returned from exile to be elected Prime Minister of Bulgaria from 2001 to 2005.

- Prince Charles Philippe, Duke of Anjou (born 1973) descendant of the last King of France has lived in Cascais since 2008.[40]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Portuguese. (May 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

- ^ "Census 2021 — Provisional Results". Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ "Áreas das freguesias, concelhos, distritos e país". dgterritorio.pt. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ "Alternative Algarve". Irish Times. 8 January 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "Jornal Economico - Lisboa, Cascais e Sintra são os municípios que mais encaixam com IMI". Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ RTP, RTP, Rádio e Televisão de Portugal-António Carneiro. "Seis dos quinze concelhos mais ricos situam-se na Região de Lisboa". www.rtp.pt.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ferreira, Cristina. "Grande Lisboa é a região ibérica mais rica em poder de compra". PÚBLICO.

- ^ Villarpando, Victor (17 November 2014). "Sintra fica do lado de Lisboa e tem a maior cara de conto de fadas". Jornal CORREIO - Notícias e opiniões que a Bahia quer saber. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Folha de S. Paulo - Mercado imobiliário em alta dá apelido de nova Miami a Lisboa

- ^ Sapo Economia - Investir 1,3 milhões de euros para vender imóveis de luxo em Lisboa

- ^ Diario de Noticias - Portugal é a nova Miami para os brasileiros ricos

- ^ "Expresso - O negócio milionário das casas de luxo em Portugal". Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ "Cascais é a terceira melhor cidade do país". Observador. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Eurodicas - Melhores Cidades de Portugal

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Câmara Municipal, ed. (2011). "História" (in Portuguese). Cascais, Portugal: Câmara Municipal de Cascais. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ "Cemitério visigótico de Alcoitão". www.patrimoniocultural.gov.pt. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ d'Encarnação, José (1979). História e geografia de Cascais (PDF). Cascais: Publigráfica.

- ^ Cardoso, J.L; Cardoso, G.; Guerra, M. F. (1995). A necrópole tardo-romana e medieval de Talaíde (Cascais). Caracterização e integração cultural. Análises não destrutivas do espólio metálico (PDF). Câmara Municipal de Oeiras.

- ^ Cardoso, Guilherme; d'Encarnação, José (2010). Património Arqueológico (PDF). Cascais: Câmara Municipal de Cascais. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-972-637-225-7. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ Diário da República. "Law nr. 11-A/2013, page 552 30" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ "Beaches of Cascais - Cascais Municipality Website". Praias | Cascais Ambiente. 2018.

- ^ O Clima de Portugal: Normais climatológicas do Continente, Açores e Madeira correspondentes a 1931-1960. Serviço Meteorológico Nacional, Observatório do Infante D. Luís (Lisboa). 1965. p. 108. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ O Clima de Portugal: Normais climatológicas do Continente, Açores e Madeira correspondentes a 1931-1960. Serviço Meteorológico Nacional, Observatório do Infante D. Luís (Lisboa). 1965. p. 109. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Instituto Nacional de Estatística. (Recenseamentos Gerais da População) Archived 8 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Cascais". Cascais Invest: economic promotion and investment unit. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ "Taxa turística de um euro cobrada em Cascais a partir de hoje". Diário de Notícias. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Kontakt"/"Contactos Archived 2017-12-17 at the Wayback Machine." German School of Lisbon. Retrieved on May 5, 2016. German: "Deutsche Schule Lissabon Kindergarten, Grundschule, Gymnasium Rua Prof. Francisco Lucas Pires 1600-891 Lisboa Portugal" and "Deutsche Schule Lissabon - Standort Estoril Kindergarten, Grundschule Rua Dr. António Martins, 26 2765-194 Estoril Portugal" ; Portuguese: "Escola Alemã de Lisboa Jardim Infantil, Escola Primária e Liceu Rua Prof. Francisco Lucas Pires 1600-891 Lisboa Portugal" and "Escola Alemã de Lisboa - Dependência do Estoril Jardim de Infância, Escola Primária Rua Dr. António Martins, 26 2765-194 Estoril Portugal"

- ^ "Contact." Saint Dominic's International School. Retrieved on December 8, 2016.

- ^ "Museum Quarter". Visit Cascais. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Cascais Cultural Centre". Visit Cascais. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Casa Duarte Pinto Coelho". Cascais. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Museu da Vila". Visit Cascais. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Geminações". cascais.pt (in Portuguese). Cascais. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ Aure Atika, IMDb Database retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Luana Piovani, IMDb Database retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Daniela Ruah, IMDb Database retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Vera Kolodzig, IMDb Database retrieved 01 July 2021.

- ^ Mariana Bandhold, IMDb Database retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ deutschlandfunk.de. "Camilla Kemp - erste deutsche Surferin bei Olympischen Spielen". Deutschlandfunk (in German). Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (29 February 2000). "Ioanna, Ex-Queen of Bulgaria, Dies in Portuguese Exile at 92". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "Prince Charles Philippe d'Orléans, Duke of Anjou". Living in Cascais. Retrieved 13 September 2019.