Buffalo '66

| Buffalo '66 | |

|---|---|

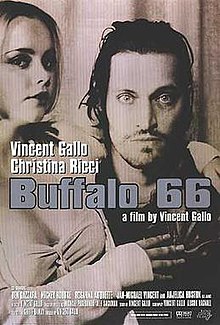

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Vincent Gallo |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Vincent Gallo |

| Produced by | Chris Hanley (credit only) |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Lance Acord |

| Edited by | Curtiss Clayton |

| Music by | Vincent Gallo |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Lions Gate Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.5 million[1] |

| Box office | $2.4 million[2] |

Buffalo '66 is a 1998 American independent romantic comedy drama[3] film directed by Vincent Gallo, who co-wrote the screenplay with Alison Bagnall, starring Gallo, Christina Ricci, Ben Gazzara, Mickey Rourke, Rosanna Arquette, Jan-Michael Vincent, and Anjelica Huston. The plot revolves around Billy Brown (Gallo), a man who kidnaps a young tap dancer named Layla (Ricci) and forces her to pretend to be his wife to impress his parents (Gazzara and Huston) after he gets released from prison, while also seeking revenge on Buffalo's kicker who he blamed for losing a championship game.

The film was generally well-received with detached praise towards Ricci's performance. Empire listed it as the 36th greatest independent film ever made.[4] It was filmed in and around Gallo's hometown of Buffalo, New York, in winter. The film uses British progressive rock music in its soundtrack, notably King Crimson and Yes.

The title refers to the Buffalo Bills American football team, who had not won a championship since the 1965 American Football League Championship Game (which was actually played on December 26, 1965). The plot involves direct references to the Bills' narrow loss to the New York Giants in Super Bowl XXV, which was decided by a missed field goal.

Plot

[edit]Having just served five years in prison, Billy Brown returns home to Buffalo, New York, and is preparing to meet with his parents, who do not know he has been in prison. He kidnaps Layla, a tap dancer, and forces her to pretend to be his wife to his parents. He gives her the name "Wendy Balsam".

When they meet with Billy's parents, Layla sees that the relationship between them is very dysfunctional, seeing Billy's mother forgetting he has a chocolate allergy and his father behaving inappropriately toward her. She learns that Billy's mother has never missed a Buffalo Bills game, except in 1966, on the day Billy was born. In a flashback, it is revealed that Billy once placed a reckless $10,000 bet on the Bills to win Super Bowl XXV; when they lost, the bookie forced Billy to clear his debt by confessing to a crime he did not commit, resulting in his time served in prison. Now, Billy seeks revenge on Scott Wood, the kicker who lost the game.[a]

As they leave his parents' house, Billy scolds Layla for telling an obvious lie to his father, and then decides to go bowling. There, Billy shows off his expertise at the sport, and Layla performs a tap dance routine to King Crimson's "Moonchild". The two use a photo booth to take photos "spanning time" which Billy intends to send to his parents once a year, but Billy becomes annoyed when Layla makes silly faces during the photos, in contrast to Billy's straight face.

After bowling, Billy and Layla visit a diner, where Billy encounters the real Wendy Balsam, a woman he used to have a crush on in middle school, who is now happily in a relationship with another man. Billy leaves Layla alone in the diner after a brief argument, but regretting his outburst, returns and apologizes to her. Billy and Layla check into a motel, where Billy and Layla have a deep conversation, and eventually admit that they have fallen in love with each other, and they both go to sleep.

A few hours after midnight, he is about to leave to exact his revenge on Wood, when Layla awakens. Despite Layla's doubts that he will return and proclamation of her love for him, he leaves, lying to her that he will return in a few minutes with hot chocolate for her. Shortly after leaving Layla at the motel, Billy calls his best friend Goon (who prefers to be called Rocky) and gives him the combination to his locker. Billy then hangs up and finds Scott Wood, now the owner of a topless bar. At the bar he walks over to Wood's table and shoots him before shooting himself. His parents are then shown sitting by his grave with his mother more interested in a Buffalo game on the radio than in her own son's death. However, this is all shown to be in Billy's head, and he leaves the bar without shooting Wood. Billy realizes that in Layla he has found someone who truly loves him. After making amends with his friend Goon on a payphone, Billy elatedly buys Layla her hot chocolate and a heart-shaped cookie, and buys another for a man sitting nearby who tells him he has a girlfriend, before returning to Layla at the motel.

Cast

[edit]- Vincent Gallo as Billy Brown

- John Sansone as young Billy Brown

- Christina Ricci as Layla

- Ben Gazzara as Jimmy Brown

- Mickey Rourke as the bookie

- Rosanna Arquette as Wendy Balsam

- Jan-Michael Vincent as Sonny

- Anjelica Huston as Jan Brown

- Kevin Pollak and Alex Karras as TV sportcasters

- John Rummel as Don Shanks

- Bob Wahl as Scott Wood

- Penny Wolfgang as the judge

- Michael Maciejewski as the guy in the bathroom

- Carl Marchi as the cafe owner

- Kevin Corrigan as Goon/Rocky (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Gallo wrote the first draft of the script in 1989, initially involving a character trying to win a big part in a movie. Among other motivations such as his hometown Buffalo Bills losing Super Bowl XXV in 1991, Gallo rewrote the script. The screenplay is credited to Gallo and Alison Bagnall, who he contended that was "really was my typist for a couple of weeks, and I had to give her that credit because I didn’t get her to sign anything first."

The film was originally set to be directed by filmmaker Monte Hellman. However, disagreements between Gallo and the film's producers (who wanted to wait for snow to fall) led to Gallo deciding to direct the film himself.[6]

During filming, Gallo had difficulties working with his cast and crew, and reportedly did not get along with Ricci on set. Gallo called Ricci a "puppet" who did what she was told.[7][8] Ricci vowed never to work with Gallo again.[9] She also resented comments Gallo made about her weight three or four years after filming.[10] Anjelica Huston also had issues with Gallo,[11] and Gallo claimed Huston caused the film to be turned down by the Cannes Film Festival.[11] After Gallo fired original cinematographer Dick Pope, director Stéphane Sednaoui suggested Lance Acord, though Gallo has claimed credit for designing most of the film's cinematography, saying Acord was simply a "button pusher" who had "never shot a feature film in his life".[12][13] Gallo also publicly disparaged Acord, saying, "This guy had no ideas, no conceptual ideas, no aesthetic point of view."[14][11] Kevin Corrigan chose to opt out of the credits because he did not want to be associated with the film at the time.[15]

Gallo was unable to use real NFL logos or to refer to the team as the "Buffalo Bills"—just "Buffalo" or "the Bills"—as NFL Properties was uncooperative. Kicker Scott Norwood was invited to participate in the film but declined, meaning Gallo had to change the character's name to Scott Wood.[16]

The film was made for just under $2 million. It was filmed on reversal stock to give it a classic look similar to that of NFL Films reels from the 1960s, with high color saturation and contrast.[16]

Gallo has stated that despite popular misconception, the film "isn't autobiographical in any real way. Yes, the parents are based on my mother and father, but that's a conceptual gimmick. People often diminish the multitasking on that film by calling it autobiographical. The interesting thing about me is that I don't relate to Billy Brown in any way, because I don't take that abuse in any other form." He also expressed a "big catharsis in writing the script, and an even bigger one making the movie."[17][18]

Music

[edit]Most of the film's score was composed and performed by Gallo himself. The score features re-recordings of four tracks that first appeared on the soundtrack for The Way It Is, which was released in a limited vinyl-only edition in 1992.

The soundtrack also makes use of several other songs, including "Fools Rush In (Where Angels Fear to Tread)" by Nelson Riddle in a cover version performed by Gallo's father Vincent Gallo Sr., "Moonchild" by King Crimson, "I Remember When" by Stan Getz, and "Heart of the Sunrise" and "Sweetness" by Yes.

Themes and analysis

[edit]Gallo, who is a political conservative, has stated that Buffalo '66 is a political film. In an interview with filmmaker Caveh Zahedi, Gallo stated:

"In Buffalo '66, the idea was of this extremely misguided victim who saw himself as a victim in the most unreasonable, unrealistic ways. That his life transforms the minute he takes responsibility for his own life is a direct political statement – a very uncomfortable one for many people because socialists feel quite opposed to that."[19]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 77% based on 60 reviews, with an average rating of 7.1/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "Self-indulgent yet intriguing, Buffalo '66 marks an auspicious feature debut for writer-director-star Vincent Gallo while showcasing a terrific performance from Christina Ricci."[20] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 68 out 100, based on 19 critics, indicating "generally favorable" reviews.[21]

In Time Out New York, film critic Andrew Johnston noted: "Ricci and Huston give poignant depth to characters that could have been cartoons, and Gallo makes Billy both annoying and sympathetic with seeming effortlessness. But the film's most potent ingredient is its visual style. The film's washed-out colors and the flashbacks that explode from Billy's head like comic-book thought balloons make Buffalo feel less like a movie than a dream given form."[22] Film critic Roger Ebert gave the film a positive review, awarding it 3/4 stars, and writing that it "plays like a collision between a lot of half-baked visual ideas and a deep and urgent need. That makes it interesting."[23] Film critic Elvis Mitchell praised the film in an interview with Gallo, describing the film as "touching".[24]

The film has since gained a cult following,[25] especially in Japan.[26]

Accolades

[edit]| Award | Year | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Independent Film Awards | 1999 | Best Foreign Independent Film - English Language | Buffalo 66 | Nominated |

| Gijón International Film Festival | 1998 | Special Prize of the Young Jury | Vincent Gallo | Won |

| Grand Prix Asturias | Nominated | |||

| Gotham Awards | 1998 | Open Palm Award | Nominated | |

| International Film Festival Rotterdam | 1999 | Moviezone Award | Won | |

| New York Film Critics Circle | 1998 | Best First Film | Nominated | |

| Seattle International Film Festival | 1998 | Best Actress | Christina Ricci | Won |

| Stockholm International Film Festival | 1998 | Bronze Horse: Best Film | Buffalo 66 | Nominated |

| Sundance Film Festival | 1998 | Dramatic Competition | Vincent Gallo | Nominated |

In popular culture

[edit]- Dialogue from the film is sampled in reverse during the song "I'm Getting Closer" on M83 by the band M83.

- Swedish singer-songwriter Jens Lekman references Buffalo ‘66 in earlier recordings of his song "A Postcard to Nina". In the plot of the song, he must pretend that he is Nina's boyfriend during dinner with her parents.

- In the 2003 Japanese video game Silent Hill 3, a photograph of a young Billy Brown from Buffalo ‘66 appears as an easter egg.

- The 2011 game Catherine by Atlus loosely based its main protagonist Vincent Brooks after Gallo's Billy Brown.[27] Likewise, the eponymous Catherine is based on Christina Ricci's Layla.

- British band Wet Leg mention the film in their 2021 song "Wet Dream", in which a character propositions the singer with "Baby do you want to come home with me; I've got Buffalo '66 on DVD".[28]

Notes

[edit]- ^ This is a reference to Buffalo Bills kicker Scott Norwood, who missed the potential game-winning field goal in Super Bowl XXV.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ Smith, Andrew (September 29, 2001). "Buffalo boy". The Observer. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ "Buffalo '66 (1998)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ^ "Buffalo '66 (1998) - Vincent Gallo | Synopsis, Characteristics, Moods, Themes and Related | AllMovie".

- ^ "50 Greatest Independent Films by Empire Magazine". Filmsite. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ Imlach, Gary (January 7, 2007). "It's Super Bowl loser Norwood's unlucky number. Here's why..." The Observer. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ^ Dixon, Wheeler Winston (July 2021). "An Interview with the late Monte Hellman (1929-2021)". SensesofCinema.com.

- ^ "Director Lashes Out at Ricci". ABC News. October 30, 2000. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ^ Lee-Youngren, Tiffany (January 18, 2005). "Truth or consequences". San Diego Union Tribune. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ^ "Ricci's Traumatic Gallo Memories". Contactmusic.com. July 13, 2004. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ Calhoun, Dave (May 2007). "Christina Ricci interview". Time Out. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c Chaw, Walter (January 3, 2013). "Gallo's Humor: FFC Interviews Vincent Gallo". Film Freak Central. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ Grant, Ed (February 3, 2015). "Workshopping History: Mike Leigh on Mr. Turner". The Public. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ "Capone Takes A Shot In The Mouth From THE BROWN BUNNY'S Vincent Gallo!!". Ain't It Cool News. August 22, 2004. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ Zahedi, Caveh (September 9, 2004). ""I don't intend to be a provocateur": Vincent Gallo". GreenCine. Archived from the original on April 17, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (February 2, 2010). "Kevin Corrigan". The A.V. Club. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ^ a b Faust, M. (March 30, 2015). "From the Vaults: Vincent Gallo on Buffalo and Buffalo 66". The Public. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ^ Tobias, Scott (September 1, 2004). "Vincent Gallo". The A.V. Club.

- ^ https://www.dailypublic.com/articles/03302015/vaults-vincent-gallo-buffalo-and-buffalo-66

- ^ Zahedi, Caveh. "I don't intend to be a provocateur: Vincent Gallo". CavehZahedi.com.

- ^ "Buffalo '66". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ "Buffalo '66". Metacritic. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ^ Johnston, Andrew (June 25, 1998). "Buffalo '66". Time Out New York. p. 84.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 7, 1998). "Buffalo '66". Chicago Sun-Times – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Mitchell, Elvis (August 21, 1998). "Vincent Gallo". The Treatment (Podcast). KCRW. Event occurs at 1:40.

- ^ Peretti, Jacques (November 13, 2003). "'You are a bad man trying to do bad things to Vincent'". The Guardian.

- ^ Dipietro, Monty (August 7, 2002). "Vincent Gallo: the one that got away". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on December 9, 2021.

- ^ Catherine Visual & Scenario Collection ♀Venus☆Mode♂. ASCII Media Works. August 2011.

- ^ Golsen, Tyler (January 12, 2022). "The indie film referenced in the Wet Leg song 'Wet Dream'". Far Out. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

External links

[edit]- 1998 films

- 1998 crime comedy films

- 1998 crime drama films

- 1998 directorial debut films

- 1998 independent films

- 1998 romantic comedy-drama films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s crime comedy-drama films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s road comedy-drama films

- American crime comedy-drama films

- American independent films

- American road comedy-drama films

- American romantic comedy-drama films

- Buffalo Bills

- English-language crime comedy-drama films

- English-language independent films

- English-language romantic comedy-drama films

- Films about dysfunctional families

- Films about kidnapping in the United States

- Films directed by Vincent Gallo

- Films set in Buffalo, New York

- Films shot in Buffalo, New York

- Lionsgate films