Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

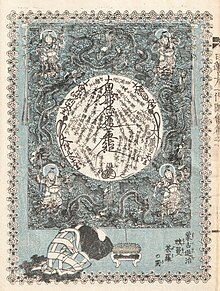

Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō[a] (南無妙法蓮華経) are Japanese words chanted within all forms of Nichiren Buddhism. In English, they mean "Devotion to the Mystic Law of the Lotus Sutra" or "Glory to the Dharma of the Lotus Sutra".[2][3]

The words 'Myōhō Renge Kyō' refer to the Japanese title of the Lotus Sūtra. The mantra is referred to as Daimoku (題目)[3] or, in honorific form, O-daimoku (お題目) meaning title and was publicly taught by the Japanese Buddhist priest Nichiren on 28 April 1253 atop Mount Kiyosumi, now memorialized by Seichō-ji temple in Kamogawa, Chiba prefecture, Japan.[4][5]

The practice of prolonged chanting is referred to as Shōdai (唱題). Nichiren Buddhist believers claim that the purpose of chanting is to reduce suffering by eradicating negative karma along with reducing karmic punishments both from previous and present lifetimes,[6] with the goal of attaining perfect and complete awakening.[7]

History

[edit]The practice of chanting the daimoku, or the title of the Lotus Sutra ("Namu-myōhō-renge-kyō"), was popularized by the Kamakura-period Buddhist reformer Nichiren (1222–1282). While often assumed to be his original innovation, historical evidence suggests that the practice existed before his time. Early references to daimoku chanting appear in Heian period (794–1185) texts, such as Shui ōjōden and Hokke hyakuza kikigakisho, where it was associated with devotion to the Lotus Sutra. Nichiren, however, transformed this practice by giving it a comprehensive doctrinal foundation and advocating it as the sole means of salvation in the degenerate age of the Final Dharma (mappō).[8]

The earliest authenticated use of "Namu-myōhō-renge-kyō" dates back to 881, in a prayer composed by Sugawara no Michizane for his deceased parents.[8] By the late 10th and early 11th centuries, the daimoku was being chanted on Mt. Hiei as an expression of devotion to the Dharma. There is evidence of the daimoku's use in sutra burials, inscriptions on statues, and other religious practices, indicating its growing significance in both monastic and aristocratic circles.[8]

During a Lotus Sutra lecture series in Japan in 1110 C.E., a tale was told of an illiterate monk in Sui-dynasty China who, since he could not read the sutra, was instructed to chant from dawn to night the phrase "Namu Ichijō Myōhō Renge Kyō" as a way to honor the Lotus Sutra as the One Vehicle teaching of the Buddha. The monk upon suicide plunged into hell then recited "Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō", which was heard by Yama who subsequently sent the monk back to life.[9]

The Kūkan (Contemplation of Emptiness), a text attributed to the Tendai monk Genshin (942–1017), states that those who "abhor the impure saha world and aspires to the Pure Land of Utmost Bliss should chant Namu Amida Butsu, Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō, Namu Kanzeon Bosatsu," which can be interpreted as honoring correspondingly the three jewels of Buddhism.[10]

Similar passages which contain the daimoku as a devotional chant is found in the works of Kakuun (953-1007), a disciple of Genshin.[10]

By the late 12th century, the daimoku began to be chanted repeatedly, similar to the nembutsu (chanting of Amida Buddha's name), as seen in records of rituals and ceremonies. Stories from setsuwa (Buddhist tales) further illustrate the daimoku's role as a simple yet powerful practice, accessible even to those with limited knowledge of Buddhism. These tales emphasize the Lotus Sutra's salvific power, suggesting that even uttering its title could form a bond with the Dharma and lead to salvation. However, the practice was not yet widespread among common people, remaining more prominent among monks and the nobility.[8]

Nichiren's daimoku practice was influenced by three key elements: earlier Heian-period daimoku practices, medieval Tendai doctrine (as seen in texts like the Shuzenji-ketsu), and the nembutsu tradition popularized by Hōnen. Nichiren synthesized these influences to create a unique and exclusive practice centered on the daimoku, which became the core of his reinterpretation of Buddhism.[8]

Nichiren

[edit]

The Buddhist priest Nichiren (1222-1282) is known today as its greatest promoter of the Daimoku in Japan. Nichiren saw it as the supreme and highest practice. In Nichiren's writings, he frequently quotes passages from the Lotus Sutra in which the Buddha declared it to be his highest teaching. These passages include: "I have preached various sutras and among those sutras the Lotus is the foremost!", "Among all the sutras, it holds the highest place," and "This sutra is king of the sutras."[11][12]

Nichiren's emphasis on daimoku as an exclusive practice paralleled the development of the chanted nembutsu, which had emerged earlier in Pure Land Buddhism. Although Tendai and other Buddhist traditions included recitation-based practices, Nichiren elevated the chanting of the daimoku to a central and universal method of attaining enlightenment. Within his early community, interpretations of the practice varied, with some followers viewing it as an expression of faith, while others understood it as a meditative discipline or a means of achieving worldly benefits. His doctrine integrated elements of Tendai philosophy, esoteric Buddhism, and contemporary concerns about the age of mappō, which contributed to its wide appeal.[8]

The Japanese Buddhist priest Nichiren was a known advocate of this recitation, claiming it is the exclusive method to happiness and salvation suited for the Third Age of Buddhism. According to varying believers, Nichiren cited the mantra in his Ongi Kuden,[13][dubious – discuss] a transcription of his lectures about the Lotus Sutra, Namu (南無) is a transliteration into Japanese of the Sanskrit namas, and Myōhō Renge Kyō is the Sino-Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese title of the Lotus Sutra (hence, Daimoku, which is a Japanese word meaning 'title'), in the translation by Kumārajīva. Nichiren gives a detailed interpretation of each character (see Ongi kuden#The meaning of Nam(u) Myōhō Renge Kyō) in this text.[14]

The Lotus Sutra is held by Nichiren Buddhists,[15] as well as practitioners of the Tiantai and corresponding Japanese Tendai schools, to be the culmination of Shakyamuni Buddha's fifty years of teaching. However, followers of Nichiren Buddhism consider Myōhō Renge Kyō to be the name of the ultimate law permeating the universe, in unison with human life which can manifest realization, sometimes termed as "Buddha Wisdom" or "attaining Buddhahood", through select Buddhist practices.

Word-by-word translation

[edit]Namu is used in Buddhism as a prefix expressing taking refuge in a Buddha or similar object of veneration. Among varying Nichiren sects, the phonetic use of Nam versus Namu is a linguistic but not a dogmatic issue,[16] due to common contractions and u is devoiced in many varieties of Japanese words.[17] In this mantra, the Japanese drop the "u" sound when chanting at a fast pace, but write "Namu", seeing as it is impossible to contract the word into 'Nam' in their native script.[16]

Namu – Myōhō – Renge – Kyō consists of the following:

- Namu 南無 "devoted to", a transliteration of Sanskrit námas meaning: 'obeisance, reverential salutation, adoration'.[18]

- Myōhō 妙法 "exquisite law"[3]

- Myō 妙, from Middle Chinese mièw, "strange, mystery, miracle, cleverness" (cf. Mandarin miào)

- Hō 法, from Middle Chinese pjap, "law, principle, doctrine" (cf. Mand. fǎ)

- Renge-kyō 蓮華經 "Lotus Sutra"

Alternative forms

[edit]In some Tendai litrugy, the sutra is praised with a slightly different phrase:

Japanese: Namu byōdō dai e ichijō myōhō renge kyō (南無平等大會一乘妙法蓮華經)

English: Homage to the Great Assembly of Equality, One Vehicle, the Wondrous Dharma Lotus Sutra.

However, Tendai Buddhism generally does not use this phrase as a repetitive chant, as the Daimoku is used in Nichiren Buddhism.

References in visual media

[edit]- 1947 – It was used in the 1940s in India to commence the Interfaith prayer meetings of Mahatma Gandhi, followed by verses of the Bhagavad Gita.[19][20][21][22][23]

- 1958 – The mantra also appears in the 1958 American romantic film The Barbarian and the Geisha, where it was recited by a Buddhist priest during a cholera outbreak.[citation needed]

- 1958 – Japanese film Nichiren to Mōko Daishūrai (English: Nichiren and the Great Mongol Invasion) is a 1958 Japanese film directed by Kunio Watanabe.[citation needed]

- 1968 – The mantra was used in the final episode of The Monkees to break Peter out of a trance.[24]

- 1969 – The mantra is present in the original version of the film Satyricon by Federico Fellini during the grand nude jumping scene of the patricians.[citation needed]

- 1970 — The film Dodes'ka-den, wherein the mother of Rokuchan in the opening scene chants vigorously, and he asks for the gift of higher intelligence.

- 1973 – In Hal Ashby's film The Last Detail, an American Navy prisoner, Larry Meadows (played by Randy Quaid), being escorted by shore patrol attends a Nichiren Shoshu of America meeting where he is introduced to the mantra; the Meadows character continues to chant during the latter part of the film.[24]

- 1979 – Nichiren is a 1979 Japanese film directed by Noboru Nakamura. Produced by Masaichi Nagata and based on Matsutarō Kawaguchi's novel. The film is known for mentioning Jinshiro Kunishige as one of the martyrs persecuted, claimed to whom the Dai Gohonzon was inscribed by Nichiren in honor of his memory.[citation needed]

- 1980 – In Louis Malle's acclaimed film Atlantic City, Hollis McLaren's Chrissie, the pregnant, naive hippie sister of main character Sally (Susan Sarandon) is discovered hiding, fearful and chanting the mantra after witnessing violent events.[24]

- 1987 – The mantra is used by the underdog fraternity in the film Revenge of the Nerds II in the fake Seminole temple against the Alpha Betas.[24]

- 1987 – In the film Innerspace, Tuck Pendleton (played by Dennis Quaid) chants this mantra repeatedly as he encourages Jack Putter to break free from his captors and charge the door of the van he is being held in.[24]

- 1993 – American-born artist Tina Turner through her autobiographical film What's Love Got To Do With It details her conversion to Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism in 1973. In a scene, after an attempted suicide, Turner begins to chant this mantra and turns her life around.

- 1993 – In the December 9, 1993 episode of The Simpsons entitled "The Last Temptation of Homer", Homer Simpson attempts to read notes he had written on his hand to guide him during an awkward conversation with a colleague, but the notes have become smeared because of sweat. In his attempt to recite his notes, Homer unknowingly babbles the chant.[25]

- 2019 – The documentary film, Buster Williams, From Bass to Infinity, directed by Adam Kahan. Jazz bassist Buster Williams is a Buddhist practitioner and chants with his wife during the film.[26][better source needed]

- 2021 – The documentary film, Baggio: The Divine Ponytail,[27] shows the football player Roberto Baggio meditating for recovery. He chants the mantra while meditating.

Associations in music

[edit]The words appear in songs including:

- "Welcome Back Home" – The Byrds[citation needed]

- "Nam Myo Renge Kyo" – Music Emporium

- "Let Go and Let God" – Olivia Newton-John[28]

- "Nam Myoho Renge Kyo" – Yoko Ono[29]

- "Boots of Chinese Plastic" – The Pretenders[citation needed]

- "Concentrate" – Xzibit[citation needed]

- "B R Right" – Trina (2002)[citation needed]

- "Beyond" – Tina Turner (2015) [30]

- "Cleopatra" – Samira Efendi (2020)[citation needed]

- "They Say" – Conner Reeves (1997)[citation needed]

- "Creole Lady" – Jon Lucien (1975)[citation needed]

- "Nam Myo Ho" – Indian Ocean (2003)[citation needed]

- "No More Parties in L.A." – Kanye West (2016)[31]

- "The Chant" – Lighthouse (1970)[citation needed]

- "Spend a Little Doe" – Lil Kim (1996)

- "Sha" – Ugly (UK) (2022) [32]

- "Hey Free Thinker" – Voice Farm (1991)

- "Do Things My Way" - Styx (2003)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia - Five or seven characters

- ^ SGDB (2002), Lotus Sutra of the Wonderful Law Archived 2014-05-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Kenkyusha (1991), p. [page needed].

- ^ Anesaki (1916), p. 34.

- ^ SGDB (2002), Nichiren Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Myohoji". Archived from the original on 2016-08-09. Retrieved 2016-06-14.

- ^ "Soka Gakkai (Global)".

- ^ a b c d e f Stone, Jacqueline. "Chanting the August title of the Lotus Sūtra Daimoku Practices in Classical and Medieval Japan 1998". Re-Visioning "Kamakura" Buddhism.

- ^ Stone, Jacqueline, Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism

- ^ a b Stone, Jacqueline, "Chanting the August Title of the Lotus Sutra: Daimoku Practices in Classical and Medieval Japan", Re-envisioning Kamakura Buddhism

- ^ "The Teacher of the Law". The Lotus Sutra and its Opening and Closing Sutras. Translated by Watson, Burton Dewitt.

- ^ "Former Affairs of the Bodhisattva Medicine King". The Lotus Sutra and its Opening and Closing Sutras. Translated by Watson, Burton Dewitt.

- ^ Watson (2005), p. [page needed].

- ^ Masatoshi, Ueki (2001). Gender equality in Buddhism. Peter Lang. pp. 136, 159–161. ISBN 0820451339.

- ^ "The Meaning of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo | Benefits & Miracles". Angel Manifest. 2020-01-13. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ^ a b Ryuei (1999), Nam or Namu? Does it really matter?.

- ^ P. M, Suzuki (2011). The Phonetics of Japanese Language: With Reference to Japanese Script. Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 978-0415594134.

- ^ "Monier-Williams Sanskrit Dictionary 1899 Advanced".

- ^ livemint.com (2008-04-16). "Exhibition of 'Lotus Sutra' in the capital". Livemint. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Gandhiji's Prayer meeting - full audio - 31 May 1947". You Tube and Gandhi Serve. Gandhiserve Foundation. 12 October 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Gandhi, Rajmohan. "Gandhi Voyage starts in world's largest Muslim nation". www.rajmohangandhi.com. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Gandhi, Rajmohan (1 March 2008). Gandhi: The man, his people and the empire (1 ed.). University of California Press.

- ^ Gandhi, Rajmohan. "What gandhi wanted for India". The Week. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Myo in the Media". Ft Worth Buddhas. Soka Gakkai International-Fort Worth. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "The Last Temptation of Homer". 20th Century Fox. 1993. Retrieved 2022-01-19.

- ^ "Watch Buster Williams: Bass to Infinity | Prime Video". Amazon.

- ^ "Baggio: The Divine Ponytail", Wikipedia, 2023-08-02, retrieved 2023-08-14

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Let Go and Let God". Grace and Gratitude. YouTube. November 30, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "yoko ono namyohorengekyo music video". Namyohorengekyo. YouTube. March 16, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ "Tina Turner - Nam Myoho Renge Kyo (2H Buddhist Mantra)". YouTube. 15 December 2015.

- ^ West, Kanye (24 July 2018). "No More Parties in LA". Youtube. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ "Ugly – Sha Lyrics | 1 review".

Sources

[edit]- Anesaki, Masaharu (1916). Nichiren, the Buddhist prophet. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Kenkyusha (1991). Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary. Tokyo: Kenkyusha Limited. ISBN 4-7674-2015-6.

- Ryuei, Rev. (1999). "Lotus Sutra Commentaries". Nichiren's Coffeehouse. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- SGDB (2002). "The Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism". Soka Gakkai International. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- Watson, Burton (2005). The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings (trans.). Soka Gakkai. ISBN 4-412-01286-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Causton, Richard: The Buddha in Daily Life, An Introduction of Nichiren Buddhism, Rider London 1995; ISBN 978-0712674560

- Hochswender, Woody: The Buddha in Your Mirror: Practical Buddhism and the Search for Self, Middleway Press 2001; ISBN 978-0967469782

- Montgomery, Daniel B.: Fire In The Lotus, The Dynamic Buddhism of Nichiren, Mandala 1991; ISBN 1-85274-091-4

- Payne, Richard, K. (ed.): Re-Visioning Kamakura Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press Honolulu 1998; ISBN 0-8248-2078-9

- Stone, Jacqueline, I.: "Chanting the August Title of the Lotus Sutra: Daimoku Practices in Classical and Medieval Japan". In: Payne, Richard, K. (ed.); Re-Visioning Kamakura Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1998, pp. 116–166. ISBN 0-8248-2078-9